This article explores the ways that Maintenance performance can be measured. Many of the principles covered apply to both institutional and industrial maintenance, and the differences are explained.

Topics include:

– Guiding principles for Key Performance Indicators (KPI’s)

– “Traditional” lagging and leading Maintenance KPI’s, and their pros and cons.

– Innovative KPI’s

– Maintenance audits

– Use of KPI’s and other Maintenance measurements

Introduction

Maintenance performance is very difficult to measure, as evidenced by the multitude of ways that people try to do it. This is too bad, because maintenance is expensive and should be measured and well-controlled. Unless you are selling maintenance it is easy for bad habits to develop and maintenance performance to slip without anyone really noticing, as long as overall organization performance is perceived to be satisfactory. On the other hand, when it becomes necessary to reduce costs, Maintenance is often the first target, often legitimately so but sometimes simply because it is so difficult to demonstrate how well it is performing.

Where a product is being manufactured, be it barrels of oil, tonnes of paper, cars, megawatt-hours of electricity or anything else, the reliability of the equipment used to produce that product is the best measure of maintenance performance (see “Measuring Reliability“). The next best measure is the cost of maintenance per unit of product. These two measurements need to be “balanced” (see below).

If you are an institutional manager and not producing a product that can be measured in units of output, many of the measurement principles in this article still apply but “lagging” KPI’s are more difficult to identify (see “Institutional vs industrial maintenance“).

Besides reliability there are, of course, the other important measures such as safety statistics, environmental incidents and so on, but I’ll focus here on “maintenance effectiveness”.

Measures of reliability, cost and safety are “lagging” Key Performance Indicators (KPI’s) because they are measuring the final results of maintenance activity, which, in the end, is all that really counts. The problem with most lagging Maintenance KPI’s is that it may take a very long time before some change in behaviour in Maintenance is evident in measurements of plant reliability, for example.

Based on the belief that certain behaviours in Maintenance will result in improved reliability, safety and cost performance, there are many “leading” measurements of Maintenance activity that can be used to predict changes in lagging KPI’s. Some of the leading KPI’s in common use are useful, some are useless and some are downright dangerous.

KPI principles

KPI’s, both lagging and leading, should :

1 – encourage behaviour that is in the best interest of the organization (not just Maintenance),

2 – be easy to measure,

3 – be difficult to manipulate,

4 – be “balanced”

5 – be consistent,

6 – provide enough information to show a trend and

7 – provide information that clarifies the action to be taken if the measurement is not on target.

Expanding on these 7 points:

1 – encourage behaviour that is in the best interest of the organization.

Some leading maintenance KPI’s, especially if they are linked to an incentive programme of any kind, may result in behaviour that you would like to avoid.

A good example is “Adherence to schedule”, which is a measure of the maintenance work that is done in a given period compared to the work that was scheduled to be done. If a lot of emphasis is attached to this measure productivity is guaranteed to drop because the easy way to achieve good adherence to schedule is to under-schedule by over-estimating each work order.

Expecting work to be done exactly to a schedule ignores a basic fact of maintenance, and that is there is hardly a maintenance job done for which the scope and the time it will take is exactly known before it is started. Jobs will nearly always take more or less time than expected. (see “Why is scheduling so difficult“)

In the tables that follow, a number of lagging and leading KPI’s are listed, and the extent to which each encourages the behaviour that is wanted is shown in the “Encourage desired behaviour?” column.

NOTE – Behaviour that is in the best interest of the organization also supports the Maintenance Statement of Purpose (see “The role of Maintenance“)

2 – Be easy to measure

Some information that would be useful in managing maintenance is difficult to measure. For example “Time spent waiting at the Storeroom” would be good to know but would require extensive observation to get a reliable figure. And the process of observation would almost certainly affect the result.

The easiest measures are those which are already available from existing systems. Good examples (of many possibilities) are the value of the Storeroom inventory, the number of visits to First Aid and the cost of Maintenance (a budget is just another KPI).

3 – Be difficult to manipulate

Some common KPI’s are very easy to manipulate. An example is “Percent ‘re-work'”, where re-work may be defined as maintenance work done on equipment where the same work was done on the same equipment within, say, the last 30 days. The person who reports re-work (tradesperson or supervisor) may be admitting to his/her own error, and can often easily hide the fact that it is re-work.

Some KPI’s are easy to manipulate because the measurement is not well-defined. “Percent planned work” is a good example. Maintenance work is never either just “planned” or “not planned”, it can be anywhere on a continuum from “not planned at all” to “very well planned”, and the people who know best where any job should lie on this scale are the tradespeople who do the work. Just because a Planner has ordered some material, or sometimes just because a work order is on a list, does not make it a “planned” work order.

4 – Be balanced

The best way to judge whether a KPI is balanced or not is to consider the extremes. For example, for the KPI “Storeroom inventory total value” consider the effect of reducing the inventory to zero. The result will obviously be increased time to repair failures and increased downtime (and other undesirable results), so if the Storeroom inventory is to be measured as a KPI, then the cost of downtime resulting from the lack of availability of spare parts should also be measured as the “balancing” KPI.

The problem with balancing KPI’s is that often only one of the two measures that should be in balance is easy to measure. Using the above example, Storeroom inventory is easy to measure, where “maintenance effectiveness” (which is affected by inventory levels) is hard to measure.

It is very important not to put too much emphasis on a KPI which is easy to measure and to ignore the balancing measure just because it is not. It is also wise to ensure that the responsibility for both balancing KPI’s is assigned to the same manager at the “decision-making” level. The Storeroom inventory example above provides one reason for assigning responsibility for both Maintenance and the Storeroom to the same manager.

NOTE – some KPI’s, such as Storeroom inventory, have an optimum value. To decide whether it is desirable to increase or to decrease inventory it is necessary to determine if the current inventory is above or below the optimum value. This applies to many KPI’s (see “Optimum Maintenance“).

5 – Be consistent

KPI’s should avoid conflicting measurements.

Lets consider overtime. In one plant where a major shutdown was held each year, overtime was tracked and reported as a KPI. During normal operation, overtime was considered “bad” and efforts were made to minimize it. However, during the annual shutdown, overtime was the most effective way to increase the amount of work that required the special knowledge and experience of the plant’s regular tradespeople, so was then considered to be “good”. Instead of reporting a single KPI for overtime, there should have been separate KPI’s for shutdown and non-shutdown overtime. Combining them in one KPI made the measurement meaningless.

6 – Provide enough information to show a trend

Consider a hospital where the total loss of electric power may result in the deaths of some patients. In this situation, using the number of total power outages as a KPI is of no value, because such outages must never be allowed to happen.

For such critical services, one or more levels of redundancy must be provided. If there are two back-up systems, one to supply power from a different transformer and the next to use an emergency generator, then a much more practical and useful KPI (as a measure of risk) is to record the time when there is only one or no back-up system available.

It often requires some innovation to find a lagging measure of maintenance that is useful in supporting the overall goals.

7 – Provide information that clarifies the action to be taken.

For example, measuring “adherence to schedule” gives little information that can correct low schedule adherence. However, recording the unscheduled work that is done allows direct action to be taken, by addressing the reliability of equipment that breaks down without warning, by correcting the behaviour of people who fail to submit work requests when a problem is found and so on.

Traditional Maintenance KPI’s

The following are examples of Maintenance KPI’s that are in common use, with a rating of how well they follow the first three of the above principles.

-

Lagging KPI’s.

The number in each cell is a measure of the extent to which each KPI principle is satisfied (1 low, 10 high).

| KPI | Encourage desired behaviour? | Easy to measure? | Hard to manipulate? |

| Units of production lost due to equipment reliability issues | 10/10. Reliability is the primary “product” of Maintenance and this is a fundamental measure of performance | 5/10. Measuring reliability down to the equipment level requires resources, discipline and excellent recording and analysis. | 10/10. With sound reporting occurrences can not be hidden |

| Units of production lost due to scheduled maintenance | 10/10. Encourages excellent planning of scheduled outages and also encourages maximizing the time between outages. | 8/10. All information is recorded as a matter of course. Where “found” (unscheduled) work is done during a scheduled outage, it may be desirable to call any extension of the downtime “unscheduled”. | 5/10. The scope of maintenance inspections during scheduled outage must be balanced with overall reliability. |

| Percent of time that no back-up supply for any critical service is available (scheduled) | 10/10. This is a basic measure of reliability and risk and should result in well-planned outages to minimize downtime. | 9/10. A simple measure, comparing the actual time of scheduled outages to planned time. | 7/10. A delayed start-up may not be noticed, so some control should be put in place (e.g. report on a test run of the equipment). |

| Percent of time that no back-up supply for any critical service is available (unscheduled) | 10/10. This is a basic measure of reliability and risk and should result in good PM inspections to minimize breakdowns. | 4/10. This requires a process for reporting unavailability which will require some discipline (e.g. recording the time of opening/closing of key valves and breakers). | 2/10. Failures may be the fault of those reporting which may skew this KPI. Unavailability of backup systems may be “hidden” failures and will not be noticed if not reported. |

| Cost of maintenance per unit of production | 8/10. A fundamental measure of maintenance, and must be balanced with reliability. | 10/10. All information is maintained in standard records. | 3/10. Large expenditures may be charged to capital or expense accounts with some flexibility, and it is easy to reduce costs for the short term because reliability reduction may take a long time to become apparent. |

| Overall Equipment Efficiency (OEE) | 10/10. A fundamental measure of equipment performance which takes in to account downtime, reduced operating rate and quality losses. | 2/10. Difficult to measure, especially when equipment is being operated below its rated capacity (i.e. it is not a production bottleneck). | 10/10. Difficult to manipulate, especially if measurements are automated |

| No. of accidents and environmental incidents | 10/10. Incidents and accidents should always result in actions to prevent recurrence. | 10/10. Easily measured from the incident reporting system. | 8/10. Usually difficult to manipulate but some control is needed (e.g. to ensure supervisors do not encourage people to continue working when they should not). |

-

Leading KPI’s

Leading maintenance KPI’s are, by nature, “soft” measurements and there are a large number of possibilities. Some are listed below, and again the number in each cell is a measure of the extent to which each KPI principle is satisfied (1 low, 10 high). The KPI’s listed are in no particular order.

| KPI | Encourage desired behaviour? | Easy to measure? | Hard to manipulate? |

| Hours charged to “blanket” or “standing” work orders | 8/10. Helps ensure that work that should be recorded is charged to a unique work order. However, standing work orders have a place and should be used where appropriate (see “Why charge to work orders?“)

|

9/10. The maintenance computer system should produce a report on the use of standing work orders and this should be reviewed by managers and followed up as required. | 3/10. Pressure to avoid the use of standing work orders will cause people to charge small jobs to the incorrect unique work order (undesirable behaviour) in order to get the job done (a desired behaviour). |

| WO’s without the correct asset number | 9/10. If the asset structure is correctly established this goes a long way to ensuring that the correct accounts are used for maintenance work and establishes accurate equipment history. | 6/10. Requires careful monitoring, although the maintenance computer system should be able to report on non-PM WO’s that are charged to high levels in the asset hierarchy. | 7/10. There may be a tendency to use “any old known” equipment number in an emergency because it is hard to look up the right asset number, and the value of this information may not be appreciated. |

| Backlog | 8/10. Maintaining a backlog that is close to the optimum is essential for achieving high maintenance effectiveness. | 8/10. Recorded in the maintenance computer system. Requires that all work orders are estimated. | 2/10. Easily manipulated by adjusting estimates. |

| Budgeting and reporting to the “decision-making” (supervisor) level

(See “Budgets and Cost control“) |

6/10. Generally results in good cost control but can encourage decisions which are not in the best interest of the organization. | 8/10. With a good reporting process, this should be automatic | 8/10. Difficult to manipulate, but not impossible (e.g. charging work to the wrong work order or account). |

| No. of occasions when regulated inspections are not completed by the required date. | 10/10. Encourages compliance with the regulatory inspection program. | 9/10. Simple reporting based on WO completion date. | 10/10. Difficult to manipulate. |

| Critical equipment testing compliance (“Critical PM’s”). | 10/10. This KPI puts a focus on the testing of critical equipment and could be used to encourage customers to provide access to this equipment. | 8/10. Once equipment has been identified and PM’s set up, reporting is through the PM compliance reporting process. Some of the most critical equipment (e.g. devices which isolate emergency back-up systems) may be very difficult to access for testing. | 8/10. Difficult to manipulate. |

| Material:labour ratio | 3/10. The use of this KPI as a measure of performance requires knowledge of the “correct” or target ratio. As a long-term trend it may have significance but is influenced by many factors. | 10/10. A simple measure and, as such, may be given too much importance. | 10/10. Difficult to manipulate, all source documents should be protected. |

| PM compliance (% of scheduled PM tasks and inspections completed when scheduled)

|

7/10. An excellent measurement, but only of real value if the frequency and content of PM inspections is appropriate for the equipment. | 8/10. Normally measured within the maintenance computer system, but requires prompt “completion” of PM WO’s . | 6/10. If the level of inspection is perceived to be excessive or unnecessary, “pencil testing” may occur. |

| Overdue PM’s | 7/10. Similar to PM compliance | 6/10. Requires all PM’s to have a “target completion date” related to frequency (e.g. 30% of time between PM WO generation) and a process to report late PM’s. | 6/10. If the level of inspection is perceived to be excessive or unnecessary, “pencil testing” may occur. |

| Percent of work done that is PM | 4/10. There is an optimum, and it may be very difficult to determine the optimum level.

It is worth checking this number every year or so to ensure that it is “reasonable”. |

5/10. Requires a good definition of PM, disciplined data entry and good reporting | 6/10. PM work competes with all other work in the backlog and can be delayed. |

| Tradespeople surveys | 8/10. Tradespeople are in the best position to judge planning and scheduling activities and material- and tool-management processes | 5/10. Some effort is required to conduct tradespeople surveys. | 7/10. Tradespeople’s opinions are not always totally objective |

| Operations surveys | 6/10. Properly structured, customer surveys should give an objective measure of performance upon which actions can be planned. | 3/10. Considerable effort is required to conduct customer surveys. | 7/10. Objective customer surveys can not be manipulated. Customers may not know if a loss of service is within Maintenance’s control. |

| No. of complaints | 6/10. The goal should be to prevent complaints. | 5/10. Complaints are subjective in nature and may not reflect real conditions. | 4/10. WO’s may not reflect that a job is the result of a complaint. |

| “Wrench time” (% of time tradespeople spend actually working on equipment) | 1/10. It is likely that this kind of measurement would have a strong reaction and may result in very undesirable behaviour, including “malicious compliance” | 1/10. “Hands on” time is extremely difficult to measure, and the act of measuring changes the result. | 1/10. Having “hands on” does not mean that good results are being achieved. It is very easy to “look busy”. Conversely, tradespeople who are not using tools may be performing very valuable problem-solving. |

| Schedule compliance | 1/10. Virtually guarantees reduced productivity, especially if there is high-profile reporting or attached incentives or penalties.

High productivity results from setting challenging targets (e.g. for the week’s work). However, the easiest way to get high schedule compliance is to set low targets (by over-estimating work orders), directly in conflict with productivity goals. This KPI also discourages legitimate, high-priority break-in work. |

6/10. Good compliance measurements should take in to account break-in work and requires careful monitoring.

For this KPI to be meaningful, estimates should challenge a “skilled, experienced and motivated” tradesperson. |

1/10. Extremely easy to manipulate by over-estimating work orders.

|

| Number of unscheduled jobs done each week (excluding “small jobs“) | 7/10. Recording these unschedule jobs identifies problems with equipment (short failure development time) or business processes (e.g. not requesting work until its urgent) and allows a focus on addressing these problems. | 10/10. Automatically measured by the work request origination and completion dates. | 5/10. Problems that should be addressed quickly may be put into the backlog, increasing the risk of breakdowns. |

| Percent “re-work” | 8/10. Does provide some incentive to address root causes and to adhere to good trades practice | 4/10. Requires a value in the “activity” work order field. May not know if it is re-work until the work is done. | 2/10. Very easy to hide the fact that it is re-work. |

| No. of repairs found during PM inspections | 7/10. A “raw” measure but should show a reduction if PM inspections are appropriate | 8/10. Need discipline to apply the correct coding on corrective WO’s from PM’s | 8/10. Easy to hide, but little incentive to do so |

| Time to complete work orders compared to priority (target completion time) | 7/10. Generally encourages priority work to be scheduled first. This KPI may encourage priorities to be set too low. | 6/10. Requires that all WO’s are promptly changed to “Complete” status when finished and are correctly prioritized. | 3/10. This is a measure of supervisory performance and it is the supervisor assessing priorities. Easily manipulated. |

Innovative KPI’s

Every industry and institution is different, and certain aspects of Maintenance performance may have special significance. Some examples of unique KPI’s are listed below, mainly to help generate ideas on the things that you may want to measure in your operation.

- Bearing usage

The following Maintenance responsibilities have a primary purpose of reducing stresses on anti-friction bearing load surfaces and thus extending their life:

– Lubricant selection, application and frequency

– Lubricant quality and cleanliness

– Balancing

– Alignment

– Sealing

– Cleaning

– Rebuild procedures

– Storage (both bearings and components or equipment in which they are installed)

– Handling

These functions form the core of a good mechanical preventive maintenance programme, so the effectiveness of such a programme will be reflected in the number of bearing failures. This number should closely match the number of bearings issued from the Storeroom, which provides a simple measure.

This measure can be refined by limiting reporting to bearings issued to work orders against specific items of critical plant equipment, by including bearings replaced during overhauls by outside workshops, by adjusting for bearing size, by discounting the replacement of undamaged bearings (e.g. during scheduled overhauls for other reasons), etc, as appropriate to the operation. Most of this information should reside in the maintenance computer system database and should be managed by a qualified person, such as a maintenance engineer.

Encourage desired behaviour? 10/10

Easy to measure? 7/10

Hard to manipulate? 8/10

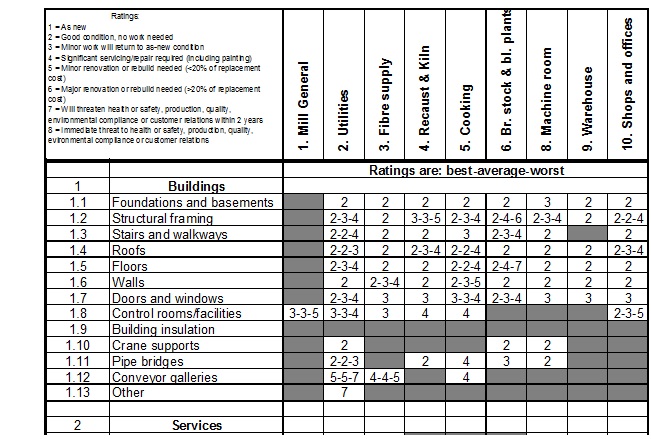

- “Level of Preservation” surveys.

Most of the “traditional” Maintenance KPI’s are relatively short-term. “Level of Preservation” surveys assess the general upkeep of infrastructure and equipment which has a long maintenance cycle, including tanks, piping, structures, roads, rail tracks and so on. The survey results in a condition report based on structured visual observations and supported with photographs. A summary of a typical report is shown below. Surveys are usually repeated on about a 2-year cycle, and provide a foundation for long-term budgeting.

Encourage desired behaviour? 10/10

Easy to measure? 4/10 – requires considerable effort.

Hard to manipulate? 10/10

- Air freight bills

When visiting a remote Canadian mining operation, a vice-president of one company would always look at the air freight bills for maintenance parts and supplies. Air freight bills were often the result of breakdowns, inadequate work planning or inventory-management problems, all undesirable conditions or events, so the volume of air freight was considered to be one measurement of maintenance effectiveness.

Encourage desired behaviour? 5/10. Too much focus on air freight costs may discourage its use when it is truly justified.

Easy to measure? 10/10 Automatically recorded.

Hard to manipulate? 6/10 Easy to use regular transport, even though it may cost the organization in downtime.

- Purchase requisitions for shutdown materials

A plant established a standard that all planning must be completed one full week in advance of the start of each shutdown. An innovative KPI was established to report all materials for shutdown work orders for which purchase requisitions were initiated later than one week before and prior to the start of the shutdown.

Encourage desired behaviour? 7/10 This KPI may discourage the late ordering of materials for which the need is identified during the shutdown preparation process or may cause shutdown work to be cancelled.

Easy to measure? 10/10 The information can be extracted from the database.

Hard to manipulate? 5/10 Materials may be incorrectly charged to non-shutdown work orders.

Maintenance audits

At times it may be of value to take a critical look at overall Maintenance results and activities, especially if there has been no consistent effort to record Maintenance performance and there is a perception that improvements are needed. Many such audits are available, including our “Five Levels of Maintenance” audit process, which we believe has some significant advantages.

If an audit is performed, it should result in an action plan and be followed up at regular intervals to ensure that the changes for which a need was identified are taking place.

Use of KPI’s and other measurements

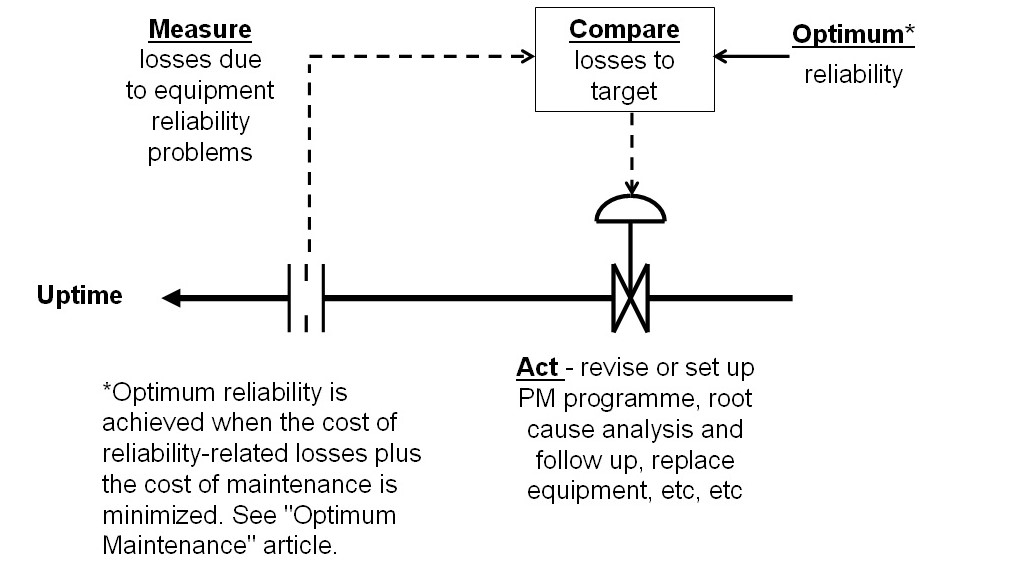

A last word about measuring maintenance performance. No measurement should be made unless it is a part of a business process that uses that measurement to create value. To manage reliability, for example, it is necessary to know what the current level of reliability is, what it should be and to have some mechanism to address the difference – just like controlling the flow of water in a pipe, as illustrated below.

This principle applies to any KPI. However, for some of the leading KPI’s in the table above, the action to take to address the difference between the measurement and the target may have zero, or even negative value for the organization. A prudent manager will watch for such measures and make sure that they are challenged.

And one very last word. A lot of very good and very bad behaviour by Maintenance people is never measured. For example, the supervisor who makes a point of having a serious discussion on safety every time he or she assigns a job is unlikely to be measured for that very valuable activity. Similarly, supervisors know which of their tradespeople can be depended on to achieve good results on their own although this may not be recorded in any document. In the end, it is up to the Maintenance leader to judge how each person is performing in all aspects of his or her job and use that knowledge wisely, along with the “measured” KPI’s, to manage the department.

Click here to return to the articles list

Management is getting people to do what you want them to do.

Leadership is getting people to want to do what you want them to do (dsa).

© Veleda Services

Don Armstrong, P. Eng (retired)

President, Veleda Services

dsarmstrong@shaw.ca

250-655-8267 Pacific Time