Related articles:

In last month’s articles I suggested that assigning serial numbers to components and tracking them to identify “rogue” parts is not a good way to ensure reliability. Rogue components are defined as components or assemblies that have a shorter service life than Original Equipment Manufacture (OEM) components.

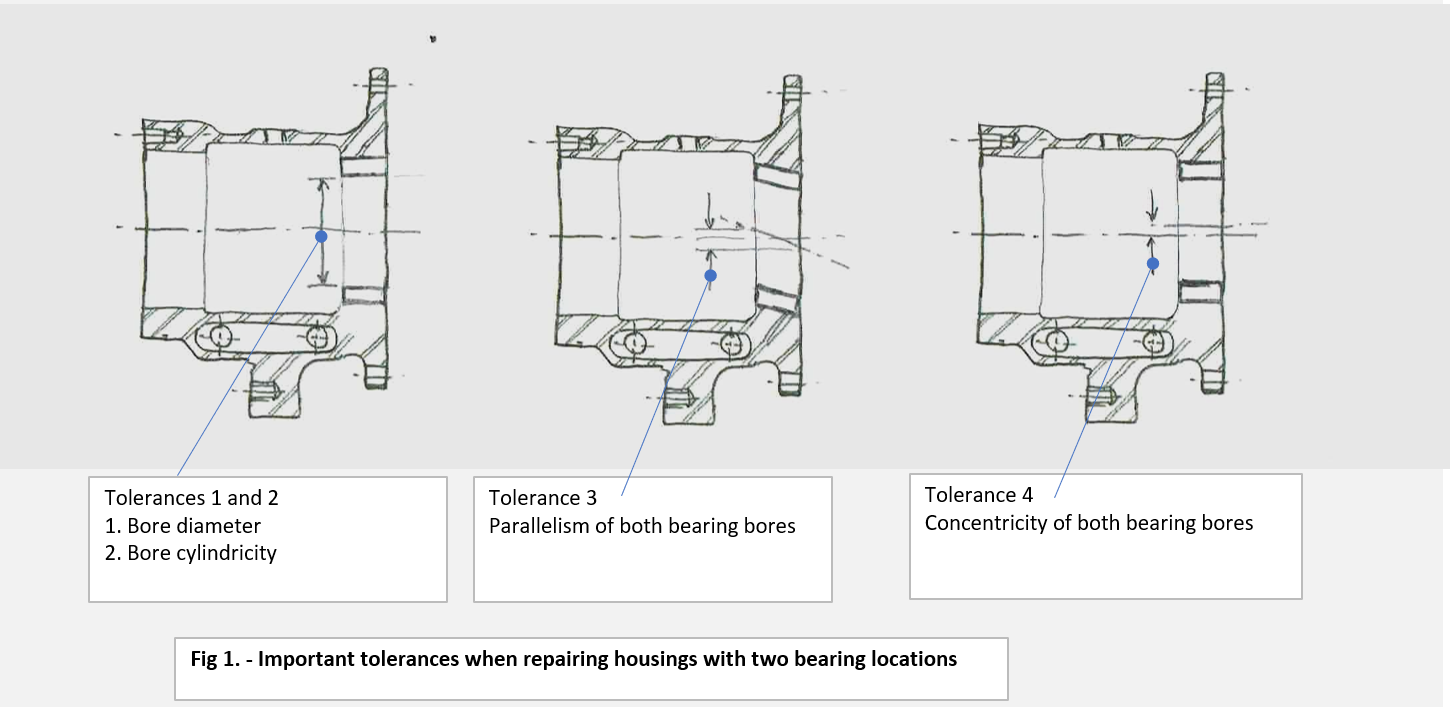

As a simple example, bearing failures in pump rotating assemblies often result in damage to the housing bore that contained the failed bearing. Because pump bearing housings are expensive spare parts, this damage is often repaired, and the repair process is usually to bore out the damaged surface, insert a sleeve, then machine this sleeve to the bore diameter recommended by the bearing manufacturer using a standard shop lathe. While this may work, it must be recognized that while this type of repair usually results in one dimension (the bore diameter of the new sleeve) being within the required tolerances for diameter and cylindricity, there are two other critical tolerances that may well be one or two orders of magnitude less accurate than in the OEM part. These are the “parallelism” and “concentricity” tolerances between the centreline of the repaired bearing bore and the centreline of the other bearing bore, and with other functional machined diameters (Fig 1). It is virtually impossible to match the bore alignment achieved in the typical manufacturer’s line-boring machine by machining just one bore in a standard lathe. Such errors, while small, may impose stresses on the bearing running surfaces that will shorten their life and may cause the repaired housing to be regarded as a “rogue”.

As materials, lubricants and machining technologies have advanced it has become possible to achieve very high reliability in much smaller components, but to maintain this reliability during shop repairs, the same standards that are followed in the OEM manufacturing process must be duplicated.

These standards do not apply only to machining accuracy. Parts must be stored and handled to the same high standards. It is not uncommon to see bearings stored with damaged protective wrapping, or to be unwrapped and exposed to a dirty shop environment prior to installation. I once observed an experienced mechanic removing a 3″ bore single-row radial ball bearing from its box by turning the box on its end about 8 inches above a steel work bench and letting the bearing fall onto the benchtop. The impact on the running surfaces probably caused more damage than many years of normal service. I’m sure that such handling was the result of a lack of training, and probably also a lack of supervision. Mechanics, Stores staff and any others involved should make a practice of handling bearings “like eggs” both before and after installation. Repaired equipment should be packaged, stored and handled the way the OEM would have done.

The same principles apply to manufacturing of spare parts, either “in-house” or by local shops. To be able to safely replace OEM parts, it is necessary to understand why they were designed the way they were and exactly what the material is. OEM’s do not normally provide this information. When a part is copied, critical dimensions can be duplicated, but it may be impossible to tell where these dimensions lay within the allowable tolerance, and if the dimensions of the copy will be within those tolerances. In one classic case, a reducer shaft and pinion were copied by a very reputable gear shop. It was assumed that the pinion should be an interference fit on the shaft and this incorrect assumption resulted in three breakdowns over an 18 month period with a production loss of over $1.5 million. The pinion should have been a close sliding fit on the shaft so that the large retaining nut would preload the pinion against a shaft shoulder, greatly increasing the fatigue strength of the assembly.

Not only is it necessary to understand the design when substitutions are made, it is also necessary to be familiar with the operating context of all the equipment in which the component may be used. For example, manufacturer’s do not use Viton seals just to increase their costs, they use them to ensure that their customers have reliable equipment. Replacing Viton seals with standard nitrile rubber seals can save money, but it can only be done with the full knowledge that they can operate reliably in the environment and conditions to which they will be exposed.

Substituting OEM parts with copied parts or parts with a different design or made of different materials is a decision that MUST be made by someone with a full technical understanding of the equipment and its operation. It is NEVER a decision that should be made by a buyer simply because of a lower price.

To return to the “Articles” index, click here.

© Veleda Services Ltd

Don Armstrong, P. Eng, President